“Knowledge Threshold” - The point at which one has no facts or data; the limit of what we currently know.

By Bill Boyd, Value Capture Client Advisor

Recently, I helped my wife build her first vlog (video blog) post. This may not seem like a large accomplishment, but this video is one that she has wanted to make for years. Years! It was created now, because I finally realized she was at her "knowledge threshold" and simply didn’t know what she needed to do to get started. I confess I thought, how hard can a vlog be, right? Just shoot some video, upload the files, adjust them as needed, open your video editing software, arrange the video clips, audio clips, titling, etc., all to her specification. Well, maybe not so simple, on second thought. To her, each step was a problem that she didn’t know how to solve. After recently hearing again about her desire to finish this project, I began to ask questions to help me understand the obstacles that prevented her from even starting this project. Over the course of a few hours, we tackled the obstacles one by one, ultimately creating the video. Once we started the process, she quickly became very adept and rapidly gained new abilities. However, until we could recognize she was at her knowledge threshold and didn’t know what to do, she was paralyzed and unable to take action.

The Principle of Embracing Scientific Thinking

I share this simple story because I see this pattern play out regularly in my work with healthcare leaders. The expectation is that leaders throughout organizations are leaders because of their expertise, their knowledge. But what happens when a leader faces a challenge they have never experienced before, when a leader is at the limit of their knowledge? Are they replaced with someone who seems to have more experience and knowledge? No, of course not.

Thankfully, there is a principle -- Embrace Scientific Thinking (from the Shingo Institute's research on enterprise excellence) -- that helps us resolve this paradigm. Scientific thinking helps us approach problems with rigor, as scientists seeking facts and data, not as experts who are supposed to “know” the answer. It helps us recognize and be comfortable acknowledging we are at our knowledge threshold, because it gives us a pattern, or kata, to follow to confront this threshold.

This may sound great theoretically, but let us consider something practical. In work, typically, people tackle problems with a full-on assault. Think about how often you sit in meetings, listening for an over-abundant amount of time, multiple people debating the “right” next step or solution. Each person conveys their thoughts, while trying to convince others to believe in their view and take their direction. As Mike Rother’s work helps us see (between 16:55-18:38 in this clip), no one in the room actually knows who or what is correct, so debate is futile. It wastes time and energy, it delays progress.

If, however, we recognized we were at our knowledge threshold and instead were thinking scientifically, we would consider what we want to try next, to learn our way to the right answer. We should debate the next experiment, not the solution.

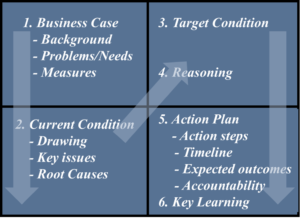

Similarly, it is not uncommon to hear people working on process improvement describe themselves as being good at “plan” and “do” (from the Plan-Do-Check-Act or PDCA cycle), but not as good at the “check” and “act” elements. I see this as a common path where well-meaning individuals have been very intent about creating perfect A3’s (problem-solving guides) to determine the “right” solution. In working the A3, the goal of the target condition (after determining root cause of the problem) is to create a new condition that solves the problems of the current condition. With the new condition defined, they feel they just need to implement and the work is done. Except, the new condition may not actually solve the problem.

The opportunity here is to consider the “action plan” as an experiment or test of the plan, rather than the implementation of a solution. Yes, there should be confidence in the newly planned target condition, but no one truly knows - yet - if the planned changes will produce the target condition and solve the problem. Thinking of our approach as an “experiment” allows for learning and possible failure, and more importantly, this allows for adapting to what is learned in the experiment.

In meeting rooms where “solutions” are debated, or in the action plan where “solutions” are implemented, the people working on the problem are at their knowledge threshold. This is a place where they simply don’t know the solution. They may think they know the solution; they may even be directionally accurate with their thinking based on experience, but in reality they don’t truly know. This is where a leader has a choice. The choice is to rely on habits built from “being the expert,” which unfortunately, leads themselves and others to wasted time, or to admit “I don’t know” and to design an experiment to learn.

Building the Habit of Scientific Thinking

We are all driven by our habits. After all, habits are what lead us to rely on “being the expert” behaviors. Coming back to the scientific method, what if we combine a habit with a principle? If we were to combine using the scientific method to solve a problem by following a simple pattern? A pattern that could help us all to recognize our own knowledge threshold, avoid wasting time in debate or going through all the effort to implement change that doesn’t actually solve a problem, but rather - a pattern of designing small experiments to test theories and then implement the solutions that do solve the problems.

This approach is rooted in Toyota kata and the study of what Toyota does each day in their patterns of problem solving. In my experience, this habitual practice using the scientific method is one potential way to learn to recognize and then work through our knowledge threshold. Of course, you would need to try this, and learn for yourself if it solves your problems. One word of advice however, once you recognize your knowledge threshold, be prepared to forever see the world differently.

If you’d like to learn more, please visit the Toyota kata website, or contact us at Value Capture, where we help leaders and their organizations systematically, scientifically pursue habitual excellence focused on safety as a precondition.

Written by Bill Boyd

Bill Boyd serves as Value Capture's Chief Operating Officer, and is responsible for business operations and overseeing all support functions. He is a seasoned healthcare professional with over a decade of practice integrating process improvement methodologies into how he leads. He is passionate about collaborating with healthcare teams to create better care experiences and outcomes for patients and families. Full Bio

Submit a comment