In recent years, we’ve seen more and more healthcare organizations adopt A3 reports and A3 thinking as their problem-solving methodology. This proliferation of scientific thinking is helping to deliver significant improvements for patients, healthcare staff, and communities in many places. However, some organizations fall into significant traps with A3 thinking, which at best, hinder individual problem-solving efforts and at worst, derail the adoption of scientific problem-solving across the entire organization. This post will highlight some of the most common pitfalls and provide actionable suggestions for avoiding them.

Pitfall #1: Jumping to solutions

Do instead: State the problem as a gap to standard

How many times have you heard someone say, “We just need to do ___ and our problem will be solved!” Unfortunately, jumping to solutions is one of the most common pitfalls with A3 thinking. Any time you hear (or read on an A3 report) things like “must do ___” or “need to improve ___”, it’s a signal that the problem-solvers might be jumping to solutions.

One way to avoid this trap is to clearly define the problem, which means stating the problem as a gap to the standard—there is no problem without a standard! To be clear, standard can mean an expectation, a goal, a norm, an objective, a desired condition, etc. Any condition that doesn’t meet the standard is a problem, whether that’s not achieving the standard, variation in meeting the standard, or requiring a higher standard than previously achieved.

A simple way to think about defining the problem is target-actual-gap. Target: What is the standard? What should be happening? What level of performance is expected or needed? Actual: What is actually happening now? What is the current level of performance? Gap: What is the difference between the standard and what’s actually occurring? For example, the problem isn’t that we need a new scheduling system, it’s:

Target: no more than 2 open appointment slots per day

Actual: averaging 4 open slots per day in June 2024

Gap: ~2 slots daily

Or,

Target: schedule 100% of our patients within 1 week of their request

Actual: currently schedule 100% of patients within 2 weeks of their request

Gap: 1 week

Once we’ve clearly stated the problem in terms of target-actual-gap, we can then seek to better understand the current situation.

Pitfall #2: Solving problems in the wrong place with the wrong information

Do instead: Go and see where the problem actually occurs to get the facts

Another common pitfall that we see is solving problems from a conference room or from behind a desk. Unless the problem occurs in the conference room or while you’re working at your desk, you can’t solve the problem there!

Similarly, we’ll often see organizations rely on reports or data from the electronic medical record (EMR) or other sources and treat them as gospel. While data is important to our problem-solving, it is still a human-made construct that we can’t treat as absolute fact. For example, I once worked with an emergency department team where the “door-to-doc” time for fast-track patients was averaging less than 10 minutes, confirmed by data from the EMR, yet they were getting many patient complaints about waiting too long. Observation revealed that some of the emergency physicians were signing up for multiple patients at once, which would record 0-minute “door-to-doc” times in the EMR for each of those patients; however, only the first patient had actually seen the doctor, and the second, third, or even fourth patients were all sitting there waiting!

On the other end of the spectrum, we’ll see problem-solving efforts that stem from anecdotal reports. Someone might complain that “___ ALWAYS happens” or “___ is NEVER done right” without turning the anecdote into something objective by quantifying the problem.

What we really need are facts, which we can only gather by going to the place where the problem occurs, making direct observations of what happens there, and interacting with the people who experience the problem. I like to think of it as a crime scene investigation—evidence is perishable. Consequently, we must respond rapidly to solve problems as close as possible to when they occurred, in the place where they occurred, and connect directly with the people involved.

Pitfall #3: Not engaging the right people

Do instead: Directly involve the people who do the work/experience the problem

Another pitfall we often see is not getting the right people involved in problem-solving. Unfortunately, sometimes A3 thinking becomes a leaders-only activity, where directors, managers, and/or supervisors effectively end up imposing “solutions” on teams rather than engaging them in improvement. Worse yet, sometimes well-meaning but misguided improvement coaches do the problem-solving on behalf of the leaders. Some organizations even lock away A3 thinking behind complex project intake and/or chartering processes that make it extremely difficult for frontline staff to get involved, or even want to do so because the barriers to entry are so high. Each of these traps is harmful to creating a culture of continuous improvement—everyone, everywhere, every day improving their work.

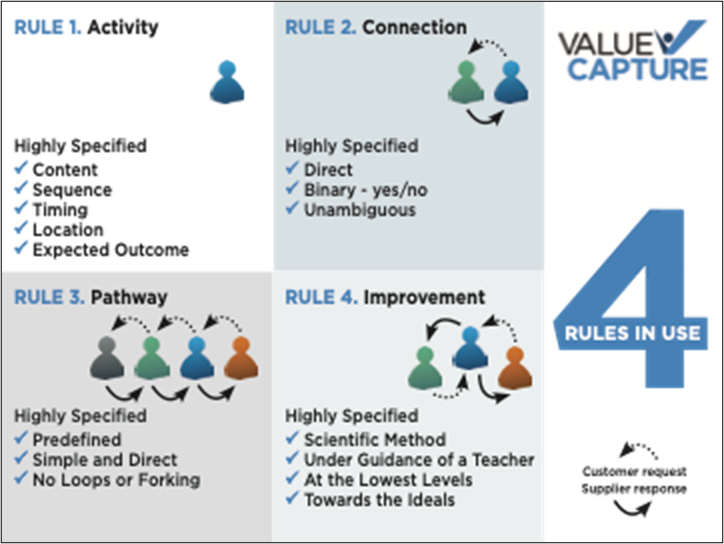

The Rules in Use, a.k.a. the principles for designing, operating, and improving all work, provide a powerful framework for problem-solving. Rule 4, the Improvement Rule, tells us that all improvements must be made using the scientific method, under the guidance of a teacher, at the lowest possible level in the organization, towards the ideals. While there is much to unpack in Rule 4, in the most simplistic terms, what it means is that the people who do the work and experience the problem must be the ones who work on solving the problem, with coaching and support from their leader. A3 thinking is for everyone!

Read more about the Rules in Use in the Harvard Business Review

When I worked in operations management at Alcoa, it was common to see frontline machine operators and material handlers writing A3 reports when they experienced problems. In fact, I first learned about A3 thinking from a veteran machine operator whom I supervised. On my very first nightshift with my team, we had a problem on the hot rolling mill, and I asked the operator how we solve problems here; he responded that we use A3s, proceeding to pull out an A3 template and show me what he meant.

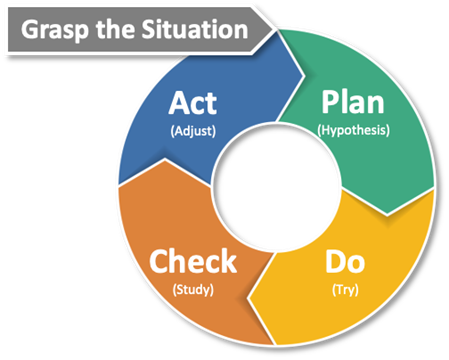

Now, Alcoa was an organization that had a very mature culture of organizational excellence at the time, so we can’t expect this sort of engagement to happen right way in healthcare organizations where A3 thinking is new to many people. However, what we can do is ensure we have frontline staff involvement in every A3, and we can teach people about scientific method problem-solving through Plan-Do-Check-Act learning cycles to run experiments aimed at improving their work.

Pitfall #4: Making it about the tool or template

Do instead: Emphasize scientific thinking and learning

Some organizations put too much emphasis on tools and templates. In fact, we’ve seen a few places where arguments about which A3 template to use become so crippling that people are barely solving problems at all! Another failure mode is solving problems unscientifically using traditional fire-fighting methods, then taking credit for A3 thinking by shoe-horning information into an A3 report after the fact.

With problem-solving, what really matters is using the scientific method and the thinking and learning process around it. Whether your organization subscribes to Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA)/Plan-Do-Study-Adjust (PDSA), Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control (DMAIC), Problem-Cause-Solution-Action-Measure (PCSAM), or something else, it’s all about analyzing problems scientifically and learning from testing hypotheses via experimentation. It is not about the tool or template you use. To me, an A3 template is like a set of training wheels on a bike—the template helps guide us and keep us from falling off the path while we’re learning to solve problems more effectively.

Rather than worrying about which template to use or whether people are filling them out correctly, focus on the thinking process behind the problem-solving and whether people are learning from the problem-solving. Here are some helpful questions to consider:

- Is the problem defined in terms of a gap to a standard?

- Has the current condition been understood through direct observation and engaging the people who do the work?

- Has the problem been broken down and the root cause(s) identified?

- What is the hypothesis?

- Do the countermeasures address the root cause(s)? Test this by asking, if the countermeasures work, will they prevent the root cause from happening again?

- Has an experiment been run to test the hypothesis and countermeasures?

- What has been learned from the experiments?

- Based on the learnings, what will be done next?

Pitfall #5: Picking “low-hanging fruit”

Do instead: Think systemically

Recently, an improvement coach at a large academic medical center told me about an A3 she was coaching aimed at decreasing the time it took to hire a new employee, which had been taking 110 days on average. Unfortunately, the team spent so much time analyzing and debating potential causes with a fishbone diagram and developing long lists of action items to address the “low-hanging fruit” that progress had ground to a halt. In fact, the analysis paralysis was so bad she had been working with the team for over a year and it was still taking about 110 days to hire a new person. Trying to “pick the low-hanging fruit”—i.e., solve many small problems—had made the problem-solving effort more complex, not yielding any measurable improvement in a process that desperately needed it. We’ve seen similar pitfalls in many other problem-solving efforts and organizations.

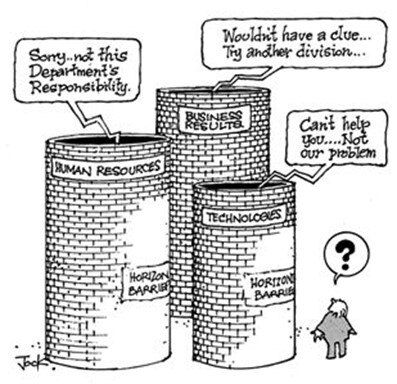

Some might blame the coach, the leaders, or even the team members for how they were managing the work or for not getting the action items done, but the real issue was that the team was working in siloes on small problems and not addressing the bigger barriers to flow across the system. For example, the recruiters were diligently working on providing better information to candidates via new email templates, but at that time, no one had recognized that candidates were receiving double-digit messages from various roles across the hiring process, sometimes with conflicting information, or that if candidates missed a particular instructional email (they would regularly get lost in junk mail folders), they wouldn’t be able to complete later parts of the process.

Again, the Rules in Use are very helpful here. Using the 5-Why technique, try to classify each potential root cause as a violation of one of the four Rules. Said another way, if you can spot a violation of one of the Rules, then it’s a signal you’ve identified an actionable root cause. Now, when you look at the root causes, you only have four problems to solve (Pathways, Connections, Activities, Improvements), not dozens! This enables people to work across siloes in a way that addresses the problem systemically across the organization rather than working on small problems within their own areas. After identifying the root cause(s) and classifying them as violations of the Rules in Use:

- Redesign the pathway so that it’s simpler and more direct, without loops and forks

- Fix connections between customers and suppliers in the pathway so that they’re direct, binary, and unambiguous; specify quantity, type, time, to, from

- Specify each supplier’s activities in terms of content, sequence, timing, location, outcome

- Specify how improvements to the new design will be made (using scientific thinking, of course!)

- Develop built-in tests to signal problems with pathways, connections, activities, and improvements in the new design

- Test the new design; when problems occur with the design, solve them as close as possible to occurrence in time, place, and person

- Apply learnings from problem-solving to improve the design

This systematic process not only solves problems more effectively but also helps to create an organizational learning culture.

In conclusion, while these certainly aren’t the only failure modes with A3 thinking, these are some of the more common ones we see in healthcare. Hopefully, your organization has avoided these pitfalls, but if not, perhaps you can improve your problem-solving capability with some of the tips here. Just remember to test your hypothesis and adjust based on what you learn!

Learn more about our Improvement Team Development Program

Learn how Aflac Insurance improved on-time delivery from 82% to 100%

Learn how Hamilton Health Sciences Built a Sustainable System for Continuous Improvement

Written by Anthony Pepe

Prior to joining Value Capture, Anthony coached at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health for five years. There he supported hospital operations, including inpatient nursing, perioperative services, the emergency department, guest services, and more. Anthony is passionate about helping healthcare executives, leaders, and team members solve problems and improve safety and outcomes.

Submit a comment