The following blog post, part 3 of 3, summarizes Ken Segel's keynote address at the annual CLEAR Symposium in Chicago on June 27, 2023.

In the first two parts of this blog series, which are based on my keynote at this year’s CLEAR Symposium, I laid out three problems that were keeping so called “lean” healthcare organizations from outperforming their peers more dramatically on the major challenges of the day.

Doubling productivity and solving the cost and labor crises in healthcare are more than possible when the framework and principles of the Toyota Production System are applied as a fully integrated system, but we observed that most ‘lean’ healthcare organizations instead do the following:

- Overemphasize the management system elements while leaving (at best) shallow implementation of the principles in the core clinical workflows of the organization.

- Fail to have operations own the approach as “the” way work is designed and operated, top to bottom.

- Overcomplicate and thus underpower their implementations.

The solution that I proposed? At one level, it’s easy to state. First, leaders – those who operate the organization - need to own the transformation and the principles top to bottom, so that there is the clear expectation that clinical operations will be built and operated to fully embed TPS principles, for example. Second, we need to act on that expectation and devote greater focus on driving the principles into the design and operation of the actual clinical work systems, with the right problem-solving structures – which change leaders’ roles – in place to support them. This should be fully supported by lean daily management systems but we need to stop relying on the management systems as the principle engine of improvement. And third, leaders have to use simple, principle-based, clear language and simple but powerful supporting structures so that everyone can understand and apply the framework at its most fundamental and impactful level in their own work. These combined, with everyone working together in a fully aligned way, allows the doubling in productivity that has been proven possible.

Easy to say, but how to get there? What would we recommend differently to leaders than the operational excellence movement in healthcare has to date to rebalance successfully? What adjustments should be made to our implementation designs?

Three Ideas for Leaders

Here are three ideas and models for experiments to “close the gap” and begin to profoundly outperform on the key challenges health systems face:

Work with leadership teams in a different way, by using the core Toyota technique of “leader looping”

We began to think deeply about the causes of why lean health systems aren’t making faster progress, and why leadership teams had over-emphasized lean daily management vs. building lean principles into the clinical flows. We analyzed the question of how effectively leadership teams were working with each other across the silos of their authority to manage the actual “horizontal” flow of clinical value in the business, and the answer was “not very.” The continuous growth of large health systems, moving senior leaders farther from the place where work is done, has added to the silo challenges (and made the silos even taller).

To counter this phenomenon in one example, our team and a health system CEO deeply experienced in TPS principles realized we had not yet built senior leader standard work around a core technique called “leader looping.”

Leader looping involves a few framing elements and then a very simple recurrent pattern.

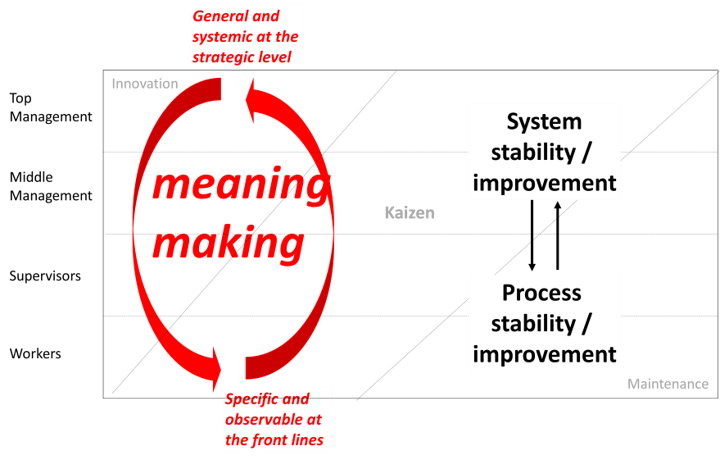

The first framing element is to help senior leaders realize that their primary responsibility for operations is to ensure end-to-end system stability, rather than ensuring that individual processes are stable. We saw a lot of senior leadership teams working individually on stability around multiple individual sub-processes. But there was very little focus and core work on naming the key end-to-end flows of the business – the vital connections across key sub-processes that deliver highest value to patients. Nor did we see much focus on adopting a system-stabilization lens for their oversight work. To get a better sense of what we mean by a system stability and performance review, you may want to refer to this classic example from Steve Spear’s observations of the TPS leader Mr. Ohba (The High-Velocity Edge: How Market Leaders Leverage Operational Excellence to Beat the Competition, Steven J. Spear).

The second framing element of leader looping is built on a key role of top leaders. They have to be able to go to where the work itself is done, see whether the TPS principles are built in or not. Leaders then must affirmatively “teach” at all levels of the organization using the principles based on the examples they observed, but then return to their system-level responsibilities and “make meaning” from what they’ve observed on the front line and sound performance information – namely, what are the implications for the system overall and their leadership related primarily to whether the TPS principles are fully in place and driving value creation or not, working across their silos?

What skills need to be built more deeply, what alignments have to deepen, what has to change in their own capabilities and standard work, to advance core SYSTEM stability. Plans are then agilely adjusted, next refinements to experiments coached in the ranks of leaders below them, and another experimental learning cycle is run to “move the measures” and increase system performance.

At the great enterprises, like Alcoa under Paul O’Neill, you see this in the top leaders – the ability to MAKE MEANING for the organization, by being able to see the smallest detail in the work (because you spend time there) and teach from it how it relates to the whole - the properties the SYSTEM has to have for success, and back and forth.

To create this focus and capability, and reach toward the “best in world” models, we needed the leaders to “learn system stability by doing,” which entailed a powerful day of “going and seeing” work and assessing it against a system-stabilizing lens, coupled with an active learning exercise so they could experience building system stability. From there, the next step was identifying a fundamental business challenge in the organization and a corresponding key flow of value across the system – such as the multiple levels of challenge facing inpatient flow, i.e., length of stay, and the detrimental impacts on the patients, people, and business case of most health systems. Once identified as the place to learn system stability, the leaders begin a “learning lab” (in this case a single large hospital) and begin working the “system” using the leader looping technique.

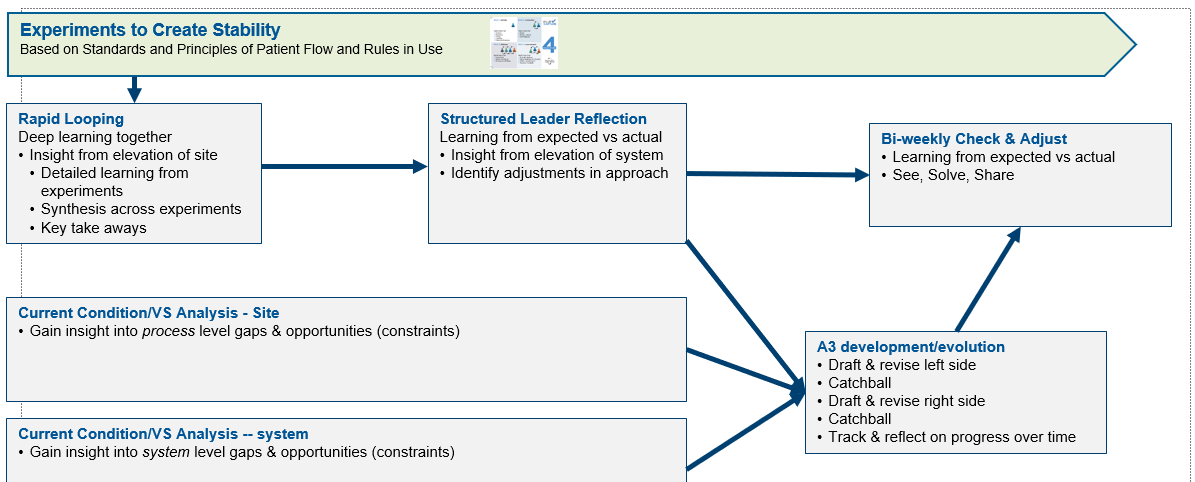

Learning Lab Using Leader-Looping Technique - Requires an Adjusted Focus

In the “learning lab” hospital the senior team learns their role and sees the profound uptick in results that the adjustments can create. Then it’s time to extend the changes to how leaders work together to the same core flow of value across the health system. In both cases, the algorithm for how the work with the senior team flows can be captured by this diagram:

Work, Improvement, and Management Systems Integration

Here is outcome data showing what results can be achieved in a few months of working in these adjusted patterns of C-suite teams being better focused on the horizontal flow of value and system stability using the leader-looping technique.

Flow with Clarity and Simplicity and Focus - The Pancake Syrup Model Explained

If “leader looping” is a fundamental technique to keep leaders focused on the horizontal flows of value across the organization, so is the “Pancake Syrup” approach to organizational transformation that I’ve teased in this blog series. It is perhaps an even simpler framework and practical set of daily foci for leaders to drive value at unprecedented levels across health systems.

As I’ve shared in previous blogs, Mike Bundy is CEO of the Midlands region for Prisma Health in South Carolina. He grew to this position and almost exactly one year ago took over the four-hospital Prisma Health Richland campus (teaching hospital, heart hospital, and children’s hospital) as part of his expanded responsibilities. In his most recent assignments, at the Prisma Baptist and Parkridge sites, their Leapfrog Safety Grades, profitability, employee engagement, and patient satisfaction scores have shot up all at the same time, with Prisma Parkridge winning a Leapfrog Top Hospital honor in 2020 and again in 2021, beginning just two years after Mike took the helm, during COVID.

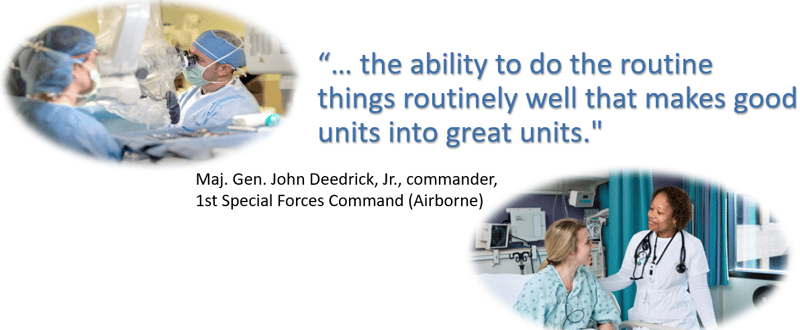

Bundy comes to us from the U.S. Army Rangers and has a knack for helping those he leads organize their work and support each other in a crystal-clear, easy-to-understand method based on a commitment to meeting the needs of patients and to meeting each other’s needs using clearly linked customer-supplier pathways. And there is no question about the purpose being to meet the needs of the human being served.

He also has a way of turning a phrase, that keeps everyone “locked in” and enthusiastic and gaining skill with the method (the image above and attributed quote is an example). He starts by telling medical staff and the rest of healthcare operations that in every root cause about things gone wrong, you always hear about time – the lack of time to do what is known, needed, and right. The answer that Bundy gives? The path to excellence lies with pancake syrup.

When Bundy responds to the question, “What do you mean,” he explains that doctors and nurses (the front-line clinical teams) are “special operators” akin to the special forces. And he says that what makes groups of special operators, and those that support them, great is the ability to do the routine things routinely well, without fail. His easy-to-understand (and remember) example is making sure that the pancake syrup ordered by a patient is on the tray at the right time, every time. When it is on the tray as ordered, the patient doesn’t ring their call bell, which takes the nurse away from doing a CAUTI bundle (or whatever it is that is the nurse’s doing-the-routine-things-routinely) to keep patients safe. This avoided call bell over syrup enables patients to heal and move through the hospital so they can get back to the safety of home as quickly as possible.

To get to this level of performance, everyone in Mike’s organization learns what he calls “micro PI” (process improvement) and with coaching, each unit uses it to identify one or two key process metrics that indicate whether they are delivering perfectly to their customers, every time.

Moreover, there is complete transparency across Bundy’s organizations, so each day starts with what he calls the “first cup stack” (named for everyone’s first cup of coffee and the “stack” of metrics clearly aligned in value streams) in which the whole team reviews the performance of the customer-supplier flows from the previous 24 hours. Crucially, any failures are being solved to root cause and worked on immediately to prevent recurrence are also shared. Not just safety failures. All failures, including missing syrup.

It is all animated by a crystal-clear purpose – to take care of patients to the highest possible standard, starting with keeping them safe, and to treat each other the same. From there, Mike is off into operations, literally, with his feet, modeling for other leaders, checking on units and people by name, always with their latest performance and praise for their efforts to be measurably great on his lips.

Using this method, Mike has seen steady performance improvement on cost, safety, throughput, employee engagement and retention, and outside measures such as Leapfrog grades, all come much faster and more sustainably than is typical in healthcare. My theory is the results come because the method is simple, fully integrated, and followed with great discipline. There is not “how the place is run” on the one hand, and lots of disconnected hard-to-grasp improvement projects or activities on the other hand.

It comes down to: System stability. Horizontal flow of value to patients. The place is led one way, for repeatable, scalable greatness, one pancake syrup packet on one tray at a time.

Yes, there’s even more to this approach – financial impacts.

At Prisma’s Richland campus, though they were in deep fiscal challenges when Mike took over, he refused to even mention finance for the first three months of his tenure, instead relying on the pancake syrup approach to produce excellence on all the key metrics at once.

Here are the Prisma Richland’s four hospital campus results for the first year of the “pancake syrup” approach, all favorable:

- Mortality down 40%

- Sepsis mortality down 50%

- Readmissions down 30%

- CLABSI down 25%

- CAUTI down 15%

- C.diff – no change top quartile

- MRSA down 15%

- With $80 million in fiscal improvement year over year.

Leader Learning Labs

Use “Leader Learning Labs” to teach leaders (and remind ourselves) what a complete and fully integrated deployment of the TPS principles looks like in a model flow – and the implications for how leaders’ jobs must change to capitalize on the ability to double productivity.

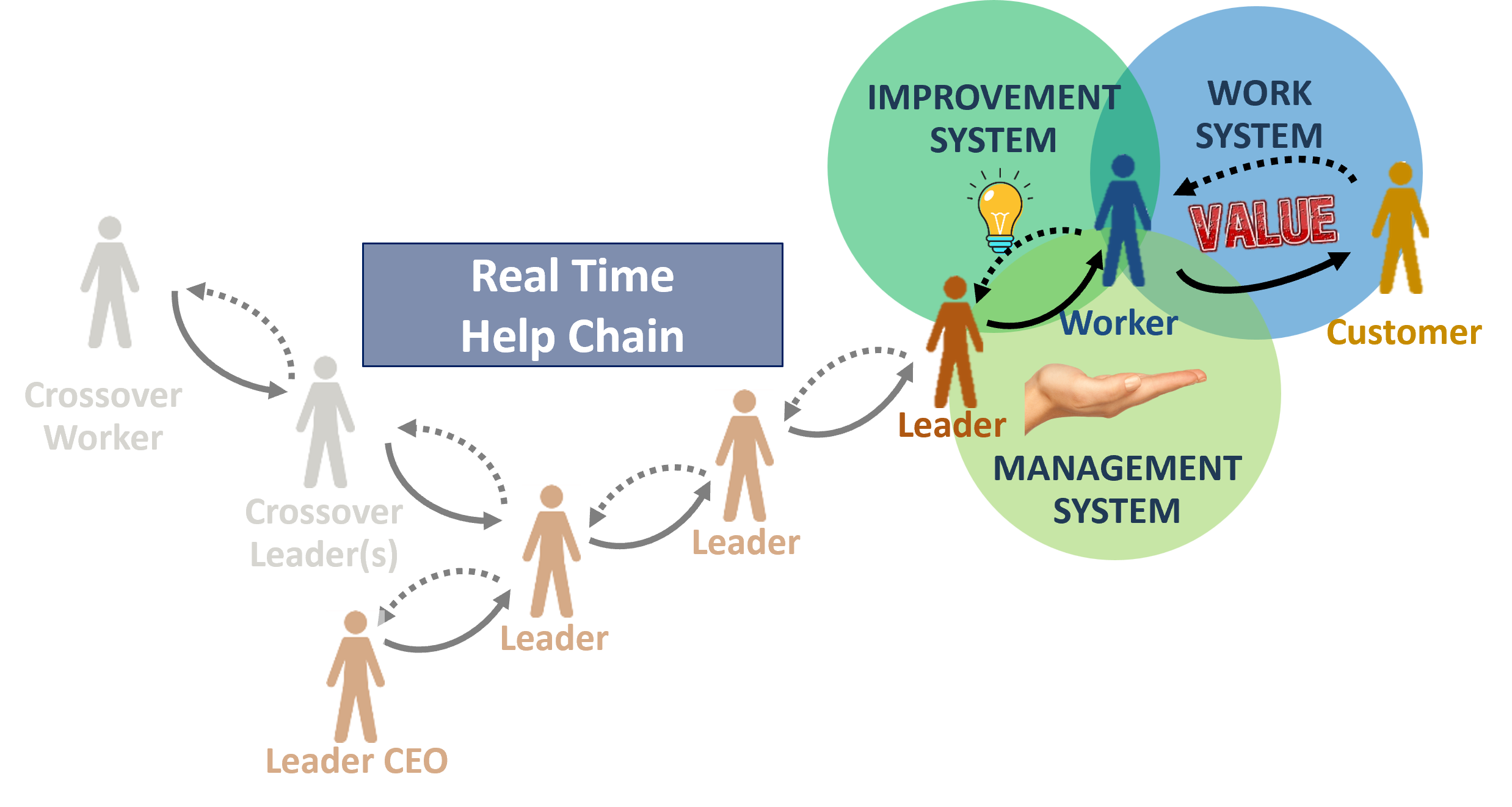

Here’s another learning. In model cells, what we call our executive learning labs, we have to make some fundamental things clearer to leaders (and perhaps ourselves) than we have. These are the places in the organization where we develop models of what it looks like when the principles are fully integrated in the work system, improvement system and management system. The learnings relate to the fact of how fundamentally the role and day to day work of leaders has to change, depending on level in the organization.

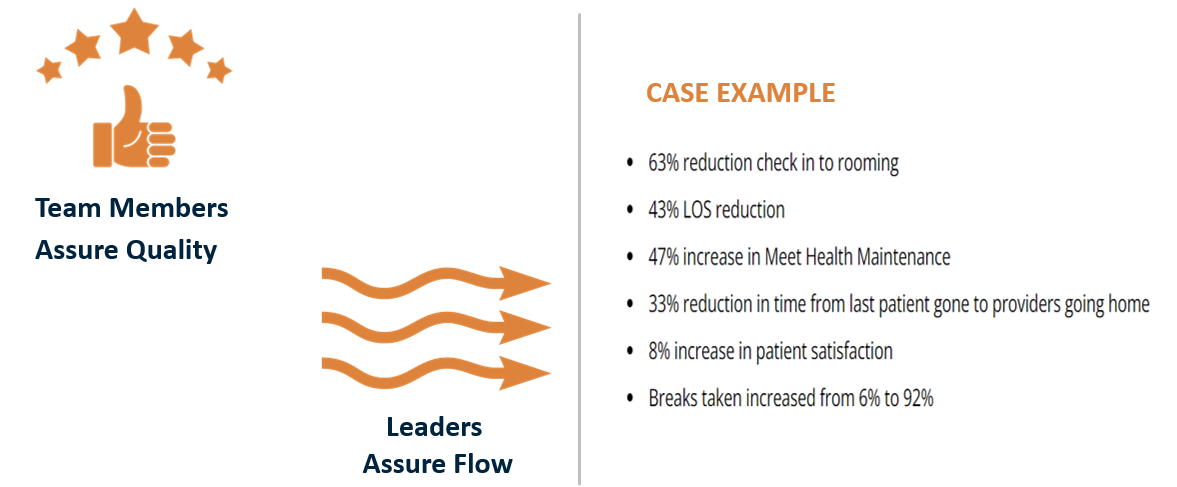

One of those learnings is that – at the root – in TPS, leaders assure flow, and team members assure quality. Flow is a leadership responsibility! That means team members’ first duty is to not pass on a defect, and to call out when a problem occurs. It’s then leadership’s responsibility to respond in real time – in a logical structure with escalation as needed built in – to restore flow. Then (ideally in real time) with those who do the work, leaders ensure the problem is solved to root so it doesn’t recur, and to spread the learnings.

We call that turning your organization chart into a real-time help chain – a lot more useful, and necessary if you are going to get the doubling in productivity. (The help chain often involves leaders in other departments; this “crossover” is often needed in order to solve problems to root).

The second learning relates to the first. There has to be a team leader – as Toyota would structure it -- and a real-time help chain in place. That means leaders’ work has to be interruptible. And the reason it has to be interruptible is that the TPS work design principles are DESIGNED to make problems visible and force them to the surface. As you get to flow, to one-by-one, on demand, you have to solve the problems that are being revealed QUICKLY. This is how you avoid problems getting baked into the system one after the other, adding complexity and frustration and waste, and in most workplaces ensuring that more than half of the workday is not spent on value-adding fulfilling work.

A Fundamental Change in the Role of Operating Leaders

Do we adequately prepare leaders to understand these truths in the experiments we set up and conduct, so they can learn, reflect on, and ultimately capitalize on the deeply radical insight, to get the productivity doubled together with so many other good things? We don’t think we do. In fact, we see an awful lot of “model cell” implementations in healthcare that embed only small parts of these most crucial elements, because there’s a sense that the current state of healthcare operations are too far away from these conditions. So of course, we get the relatively lackluster results we are getting.

Here are results from a great case study that is at once a hopeful and a cautionary tale. This was one of America’s largest health systems where we had the privilege of helping them design and test a set of model ambulatory clinics using the principles. You can see the remarkable results from restructuring and operating the clinics as TPS principles suggest.

Executive Learning Lines - All 3 Systems Working at Concert

But here’s the cautionary tale – the “buzz” from system leadership was at least as negative as it was positive, because they were “hearing about a lot of problems coming out of those model sites, problems that demanded a lot of attention to be solved.” Yes, by design. Exactly. The problems are there all day, every day in typical health system operations, whether leaders “hear about” them or not. TPS, lean, gives you the way to solve them. NOW. IF, that is, you are willing to apply the principles and structures that have already been proven, again and again, the ones that change the nature of your work. We have to make it much clearer, and give leaders the chance to see, learn, absorb, practice and convert. If we shy from the question and the corollary approach, we never get there.

What Do You Think Healthcare Leaders Should Do to Get on Track?

That’s enough from me. Now it’s time to hear from you. What do you think about these recommendations – across all three parts of this blog series, or just this one? A lot depends on all of us problem solving this challenge urgently and effectively together. Continuing the same patterns we see today won’t work.

How do you think we should get efforts to use the Toyota Production System principles in healthcare, the operational excellence movement, back on track?

Submit a comment