The following blog post, part 2 of 3, summarizes Ken Segel’s keynote address at the annual CLEAR Research Symposium in Chicago on June 7, 2023.

In Part 1 of my blog post series, “Lean Organization’s Can Massively Outperform, but Only if They Rebalance,” I explored why lean healthcare organizations should be dominating the sector by meeting the cost and labor crises much more successfully than traditionally managed health systems, but instead are only mildly outperforming.

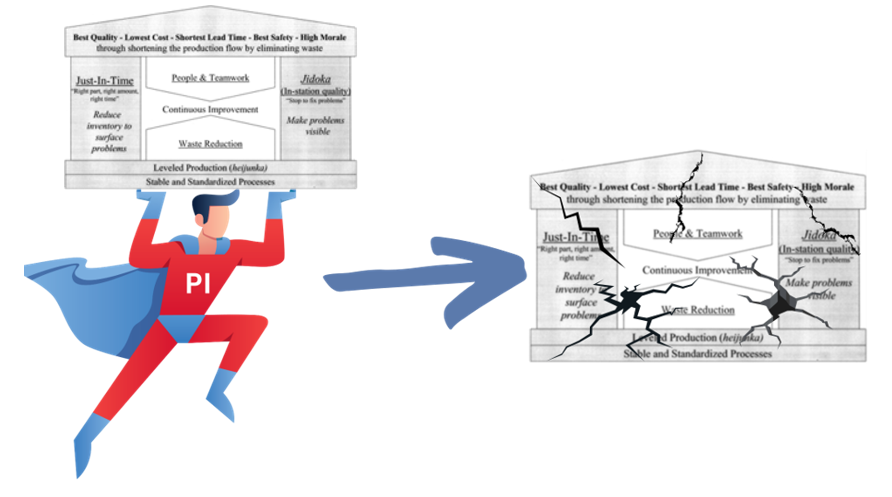

I zeroed in on how lean implementation strategy in health systems has, for more than a decade, concentrated almost exclusively on building lean daily management systems, despite that fact that health systems remain very immature in building lean principles into the design and operation of their clinical flows -- the core work system of the organization. Without a reconcentration on the work system (while maintaining the daily management system), the doubling of productivity that has been proven possible in many industries, as well as some in healthcare, will remain far out of reach.

In this Part 2 post, I want to illustrate two other problems with the past decade to present day of lean in healthcare, because these problems have to be solved at the same time as the management system imbalance.

The first is misplaced ownership. The second is overcomplication.

Misplaced Ownership

“It is not possible to delegate responsibility for habitual excellence” – Paul O’Neill, Sr.

We Never Got Ownership Right

On ownership, we never got it right. Health systems have generally failed to rest responsibility for this transformative approach squarely and fully with the operating leaders of the health system, relying instead on the performance improvement team.

Delegating lean as something to be led by, rather than supported by the expert performance improvement team guarantees a very limited ceiling of less-than-sustainable and less than impressive results for a number of reasons. These include ensuring that without executive and operational leaders leading the way, “lean” will forever be seen as “extra work,” "somebody else's responsibility," and not be “the way the organization is run.” When it’s not the way the organization is run, it is, at some level, de facto optional for leaders to fully buy in, and harder for them to do so because it’s not really the core system they are accountable for leading. Results of the projects that do get run tend to be far short of what’s possible, because they are being run with modest targets with leaders and staff whose fundamental responsibilities lie elsewhere. Sustainability of even those efforts suffers badly for the same reasons.

This means going far deeper than getting senior executives to fully honor the role of “sponsoring” kaizen (continuous improvement) events. By contrast, this means the operating executives ensuring that the Toyota Production System (TPS) work design principles (to flow and pull) are the expected condition for designing and operating their parts of the work system, in close customer-supplier horizontal flows. This means they as leaders have to be experts in the approach themselves, and that has to hold true down to the level of supervisors.

Judged by that standard, in your “lean” health system, who REALLY owns the “way?” Operations or Process Excellence? If you walked up to any director in your health system, would they describe their purpose as designing and managing operations, for example, as “pull” systems with key principles like “pass no defect” built into the work design?

To illustrate, I was talking to a CMO at a health organization that had for a while done very distinguished TPS-as-the-way work. But they had fallen off in recent years. “We now apply TPS in the following way,” he explained. “One of us in the C-suite will say, ‘performance is getting a bit out of whack at hospital X’s OR. Let’s send in the process excellence team and see if in working with the periop teams they can get things to be a little more ‘pull’ than ‘push’ so things flow a bit better.” While it is good that they want to apply the principles, it’s bad that they aren’t working the system directly and coaching to discover the problem the periop leaders are having. That organization’s executives have shifted to a delegation mentality. That’s all that most C-suites have ever had when it came to lean beyond the daily management system.

Overcomplication

In many places we see, our “lean” systems have become a bit overcomplicated, not simple and integrated, not clearly enough tied to the horizontal flow of the work across units and to the people doing the work.

There are a couple of related aspects to this. First, the language. At the three best implementations across any industry I have seen, the leaders don’t use any of the “lean” terms, other than perhaps “go and see.” These leaders know that the fancy new words can be a barrier to people clearly understanding and buying in, so they put the ideas in very plain, direct, clear language that anyone can grasp and remember and apply. These leaders know that lean terminology can be a lazy shorthand that may fail to convey the core idea. If you can’t explain it simply, ask yourself, do I truly understand it?

As an example of a great use of non-lean wording, certain leaders I know describe their operating approach, and their improvement approach, as Pancake Syrup. Yes, this does make me sound like I’m crazy, but stay tuned to part 3 of this series for an explanation.

Also, if all you can think about to help solve a problem is yet another tool, do you understand the principle well enough to explain it to the people doing or overseeing the work so they can apply the principle to tweak the tools they already have (and thereby own the problem and likely a simpler solution)?

The second aspect of this overcomplication issue is how sometimes all the activity and tools and names for tools also make it harder to track what the actual flow of value is in the system. Where are the key powerful gears linking to drive results, the ones that can double productivity?

Summary

At the great places that outperform over time, everyone can articulate the integrated system, in plain language. There is visual management, but it is honed to the essentials. It’s easy for anyone to make a diagnostic of the health of the system, often with a glance at operations ("the actual thing," to paraphrase Ohno and TPS) let alone the information visuals at five feet.

To get double the productivity and solve the cost and labor crises with TPS principles applied as an integrated system in healthcare, we need to simultaneously solve all three problems discussed in Part 1 and this post – imbalance, ownership and overcomplication.

Leaders need to own lean transformation. We need to rebalance focus on driving the principles into the design and operation of the actual clinical work systems. And we have to use simple, principle-based, plain, clear language.

I want to note that I have named just three challenges in the “lean” healthcare movement. There are others, of course. Even the best implementations, the ones that proved doubling productivity was possible, we never fully got the board of directors to know the system and own it as the key to executive succession, so we got failed successions. We need to continue that work too, but I am arguing these three linked readjustments are just as essential.

A few thoughts on how to get there – how to adjust our implementations including how we work with leadership teams to rebalance successfully, and what those health systems are starting to achieve – will be my final blog post in this series.

Submit a comment